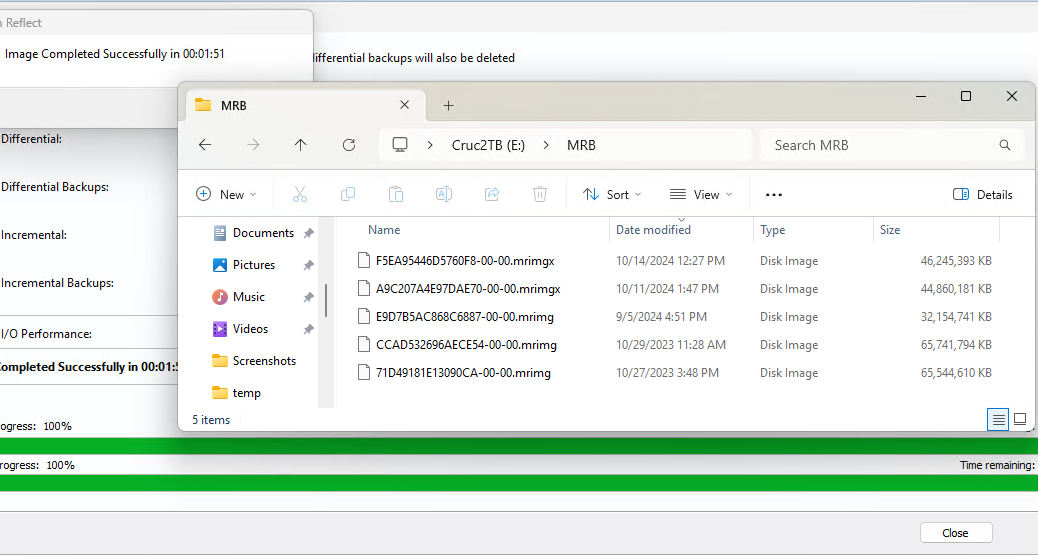

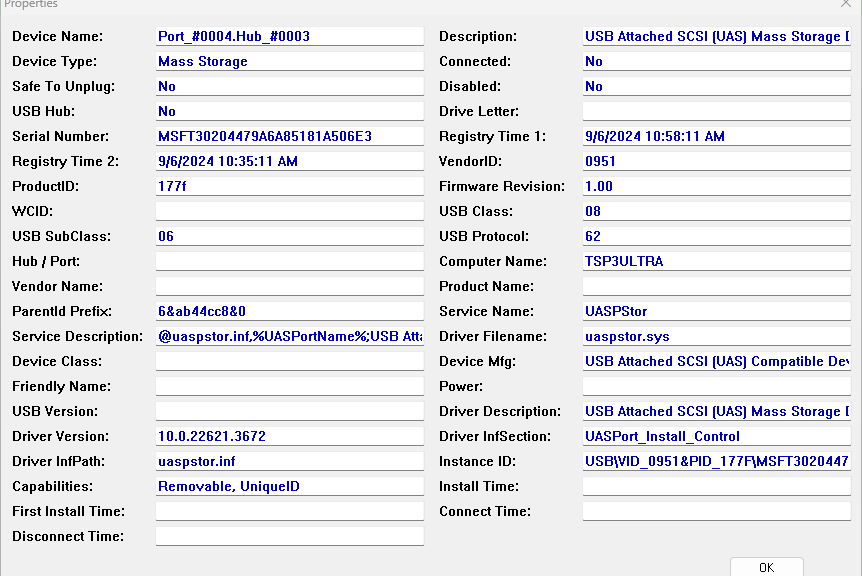

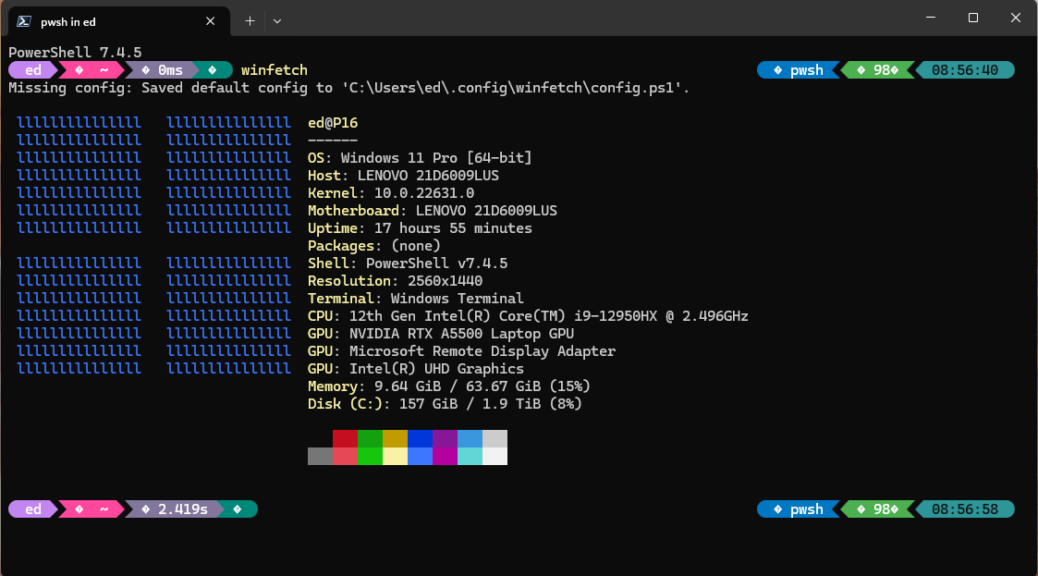

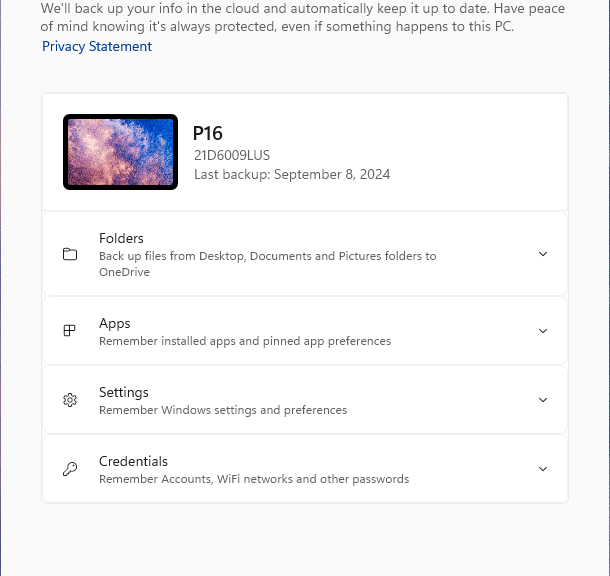

I’ve known about this for a couple of months, but until last week I was under embargo, as they say in trade press lingo. Macrium Reflect X (version 10, so it’s a Roman numeral) went public on October 8, so now I can talk. Reflect X not only backs up ARM PCs — the lead-in graphic comes from my Lenovo ThinkPad T14s Gen 6 Copilot+ PC — it does so swiftly and surely. As you can see it created a 47.24GB full disk image backup in under two minutes (1:51). But there’s more…

Why Say: Macrium Reflect X Rocks

It’s not just way speedy (it would be two to four minutes faster than version 8 for the same setup on a Wintel PC), it’s also got other things going in its favor as well. ARM support is a big deal (it’s one of a very few tools that offers scalable backup for ARM CPUs). But Macrium Reflect X also offers:

- Resumable imaging: Even after interruptions, image backup can pick up where it left off, with no data or time losses.

- Open-source file formats: Reflect has published specifications for its .mrimgx and .mrbakx file formats so other programs can use them.

- Enhanced filtering: Relect X can ignore files (e.g. contents of the Temp directory, caches, and other transient items that don’t need backing up) to reduce backup size and speed image capture time.

- Improved compression and backup optimization techniques (see this video for a backup that goes from over 8 minutes for version 8 to under 2 minutes for version X).

Reflect X Does Come at a Cost

With this latest release, Paramount Software (the company behind Macrium Reflect) has changed its licensing approach. It’s moved over from perpetual licenses plus annual maintenance fees to a pure annual subscription model. Because I had 8 licenses (4 from a 4-pack perpetual license, 4 more from a version 8 subscription purchased last year) my upgrade costs to get into Version X were right around US$200 (approximately US$25 per license per year).

I think that’s a reasonable price, but understand that new buyers won’t get as good a deal. That said, the company runs occasional specials wherein they drop list prices anywhere from 25 to 50%. Best to keep an eye out for such, if you’re planning on getting into the latest Macrium Reflect X version. IMO, it’s completely worth it, and very much the best backup/restore/repair option available for Windows PCs. You can check out a free trial for 30 days.