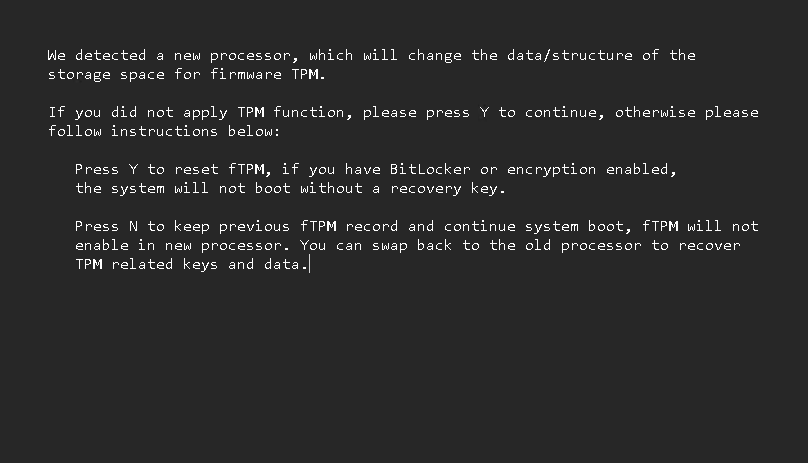

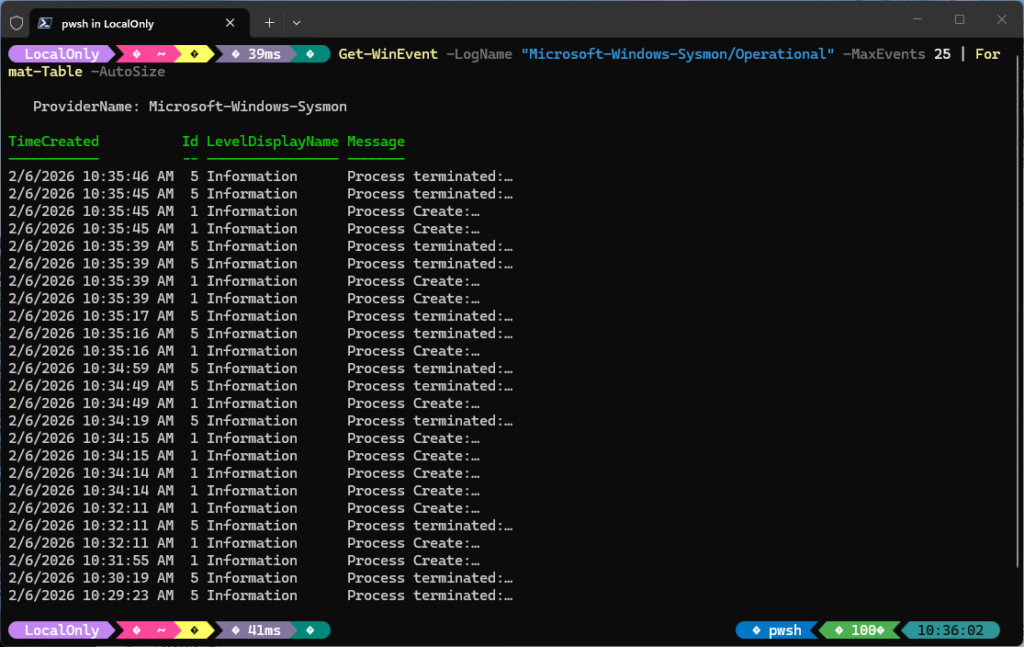

This morning I noticed external audio wasn’t working on my Flo6 desktop. I quickly went down a rabbit hole with audio drivers and such. Along the way, through a series of a half-dozen reboots, I noticed the fTPM “CPU changed” message kept popping up. At first, it was mildly annoying. But when it kept repeating I found myself stuck in a “CPU Changed” boot warning nightmare. How to escape?

Note on an AMD mobo fTPM is a firmware Trusted Platform Module, which resides inside a Platform Security Processor on the mobo. It provides the same functions as a discrete hardware TPM. It’s been bugging me lately, as I will relate…

Ending the “CPU Changed” Boot Warning Nightmare

Interestingly, the fTPM “CPU changed” message can appear even when the CPU has not been replaced. It shows up when the firmware detects a mismatch between the stored fTPM data and the state reported by the Platform Security Processor. This mismatch can happen during normal use. It can also happen after a firmware stall or a power loss. The message is confusing because it suggests a hardware change. In most cases, nothing is wrong with the CPU. The system is only trying to protect the integrity of the TPM state.

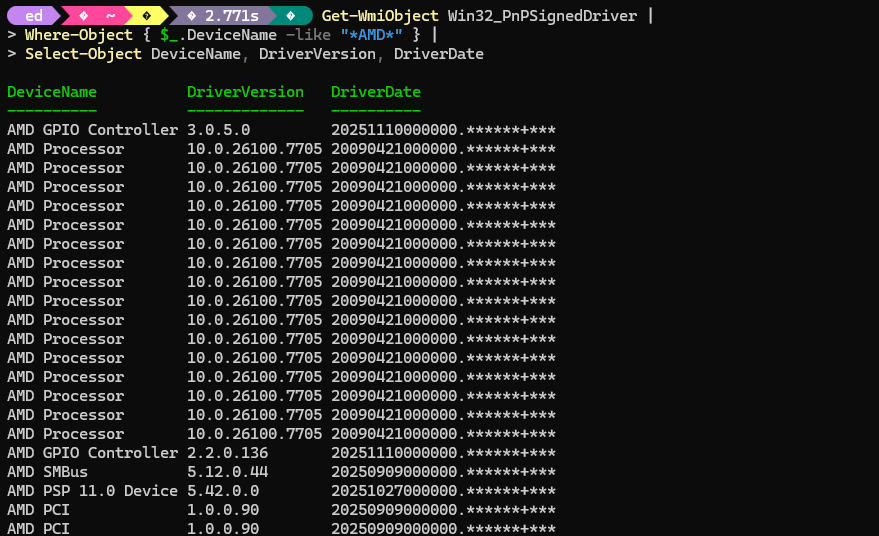

To say that Flo6 shows this message more often than other systems is an understatement. It happens a lot, and the reason is simple. Flo6 has a sensitive trust chain. It depends on the Platform Security Processor (PSP), the Embedded Controller (EC), and the BIOS staying in sync. If any part of that chain resets at the wrong time, the fTPM state can fall out of alignment. When that happens, the firmware cannot confirm that the stored TPM data belongs to the current system state. It then shows the prompt and waits for user input.

What Makes Flo6 My Problem Child?

This message appears most often after a forced shutdown. It can also appear after a firmware stall or a long power loss. If the system loses power while the PSP is active, the fTPM state may not save cleanly. On the next boot, the firmware sees the mismatch and stops to ask for confirmation. This is a safety feature. It prevents the system from using TPM data that may not match the current hardware state.

Flo6 also shows the message after a failed warm boot. A warm boot will not fully reset the PSP. If the PSP is left in a partially updated state, the next boot may not match the stored fTPM data. The firmware then shows the prompt again. This is why the message sometimes appears after a simple restart. The system is not failing. It is only trying to confirm the trust state.

Responding to “CPU Changed” with Yes

Choosing Y tells the firmware to restore the stored fTPM state. Choosing N tells it to discard the stored state. On Flo6, Y is usually the correct choice. It keeps the system stable and avoids repeated prompts. N is only valid when the CPU has changed. If the CPU has not changed, N can cause more trust state mismatches. It can also trigger BitLocker recovery if BitLocker is enabled.

The “CPU changed” message does not mean the CPU is faulty. It does not mean the BIOS is corrupted. Nor is the system unsafe. It only means the firmware wants to confirm the TPM state before it continues. Flo6 is more sensitive to this check because of the way its firmware handles power loss and warm boots.

That’s why I’m getting ready to swap the ASRock B550 Extreme4 mobo for an MSI MAG Tomahawk model. I read that its UEFI is more stable, robust, and less prone to fTPM mismatches. Here in Windows-World, an escape from the frying pan can lead into the fire. Fingers crossed that the upcoming rebuild ends this nightmare.